November 17, 2025

In the alleyways of Damascus, where the sunlight dances on stones and the air hums with centuries of memory, artist Asaad Arabi was born. His childhood unfolded in the bustling souq of Sarouja, a neighbourhood where history lived not in books but in the cadence of daily life, the rhythm of voices and the architecture of memory itself. From his earliest years, Arabi understood that memory is not static, it blends, refracts and resurfaces. As a young artist, he refused silence. His graduation project, entitled The Catastrophe of Space, criticised the interventions of French urban planner Michel Écochard in Damascus, exposing how urban ‘progress’ flattened the organic life of the city. Where others acquiesced, Arabi resisted. He explained that cities are not grids, they are music. This early work articulated the artist’s long-life creed that art must think and defend the tangible life of culture.

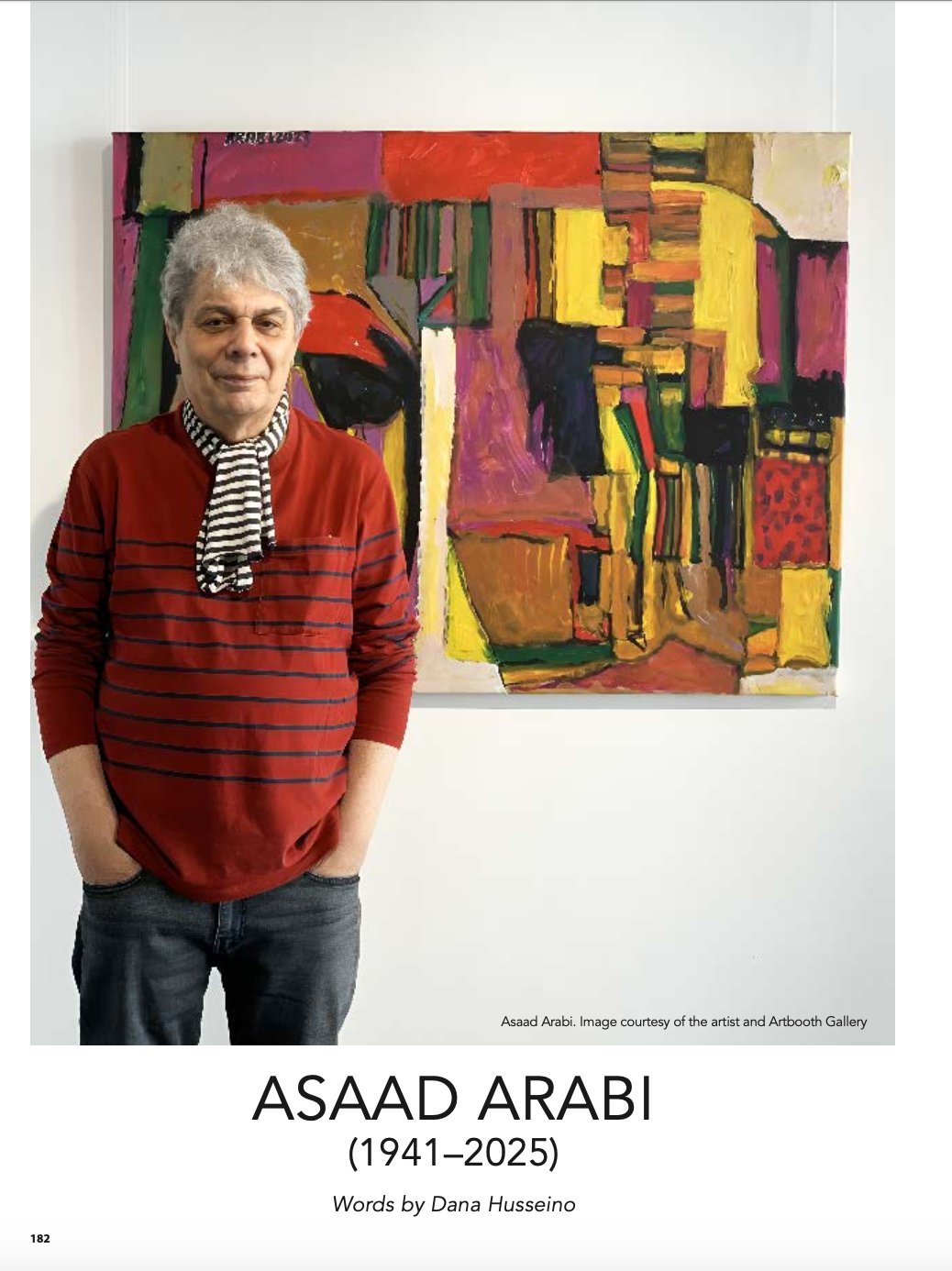

In 1975, Arabi moved to Paris, carrying the essence of Damascus with him. There, he earned a diploma in painting from the Higher institute of Fine arts and a PhD in Aesthetics from Sorbonne University. Throughout his career, Arabi’s working method reflected his belief that painting is primarily an internal activity. He explained that he cannot work on a painting if another is present nearby, preferring solitude to fully engage with a single piece. Canvases would often be moved to another room until he could be alone, carefully observing how colours intersected until the painting “calmed down”. This need for isolation made art school challenging for him, as he struggled to work within groups of drawings. This emotional depth was drawn from memory, the overlooked corners of daily life, aged walls and the remnants of authenticity.

Arabi often spoke of the shortcomings of formal art education, stressing that every child is born with an innate artistic capacity, one too easily stifled by rigid systems of schooling. He acknowledged that academies could offer valuable technical skills and methods for interpreting the visual world, yet heremained wary of instruction that became overly prescriptive. For Arabi, such rigidity risked pulling young artists way from the heart of their own expression. While he acknowledged the value of mastering skills such as anatomy and composition, he insisted that these should only serve as tools, not rules. In an interview on the show Yanabee الينابيع on Qurain TV, Arabi mentioned being influenced by figures such as Leonardo da Vinci and the French sculptor César Baldaccini. He believed that the greatest lesson an artist can learn is to forget what they have been taught and listen instead to their inner voice. By upholding the fusion of memory, intellect and emotion, Arabi provided a method and a vision that continue to instruct and inspire future generations.

Arabi’s artistic philosophy was inspired by his engagement with music. He often spoke of painting as akin to music, abstract and transcendent, where rhythm and composition governed the work as much as colour and form. This conviction was made after nearly a decade of research at the Sorbonne, where his doctoral thesis explored The Relationship Between Music and Painting in Islamic Art. A series of paintings translated this belief, particularly the voice of Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum, known as the “Star of the East”, to which he listened daily and turned into visual rhythm. Chairs, musicians and audiences were blurred into forms and negative spaces, yet her voice suffused every inch of canvas.

Through this synthesis, Arabi celebrated the Arab renaissance, known as the Nahda of the 1960s, a time defined by openness and tolerance while mourning what had been lost and imagining what could be discovered. In his painting Taqasim in a Levantine (2014), the word taqasim refers to the solo passages in Arabic where a musician departs from fixed melody into improvisational freedom, weaving tones into unexpected directions while never losing the sense of rhythm. Arabi translated this principle visually, with deep blues and greens dominating like the grounding Maqam, a traditional Arabic melodic system, while sharp intrusions of yellow, red and violet scatter across the surface, suggesting a city remembered not as geography but as sound.Asaad Arabi dedicated his life to the pursuit of art and knowledge. He enriched Arab visual culture not only through his paintings but also through his insistence that art must carry thought, critique and feeling. His final gift, perhaps, is a reminder that memory is not nostalgia but renewal, that forgetting can be as fertile as remembering, and that the pulse of a city, like the pulse of painting, continues to live, luminous, fractured and eternal.